Commonwealth of Australia Explanatory Memoranda

Commonwealth of Australia Explanatory Memoranda Commonwealth of Australia Explanatory Memoranda

Commonwealth of Australia Explanatory Memoranda[Index] [Search] [Download] [Bill] [Help]

2002-2003

The Parliament of the

Commonwealth of

Australia

Explanatory

Memorandum

Parliamentary (Choice of Superannuation) Bill

2003

The Bill amends the Parliamentary Contributory Superannuation Act 1948

(the Act) to give Senators and Members of the House of

Representatives the freedom to opt out of the compulsory parliamentary

superannuation scheme.

Retiring Members and Senators currently receive

superannuation benefits from the Commonwealth, administered

by the Parliamentary Retiring Allowances Trust (the

Trust), as established under the Act. The day-to-day administration is

undertaken by the Department of Finance and Administration.

From the

first day a Senator or Member becomes entitled to a parliamentary allowance, he

or she is automatically obliged to make contributions to the Commonwealth under

the provisions of the Act.

The Bill allows new Senators or Members to

elect not to make contributions to the Commonwealth under the provisions of the

Act upon first taking office, and instead, to make contributions to a complying

superannuation fund or Retirement Savings Account (RSA) of their choice. The

Bill gives current Senators and Members the same choice, but will also allow

them to have any superannuation benefit accrued under the parliamentary scheme

rolled-over into a complying fund or RSA of their choice.

[1] Once a new, current, or returning

Senator or Member has exercised the right to choose not to make contributions to

the Commonwealth under the provisions of the Act, he or she will not be able to

make such contributions in the future.

If a Senator or Member elects to

opt out of the Parliamentary scheme, he or she will also have superannuation

contributions paid into their chosen fund or RSA by the Commonwealth. These

contributions will be made in accordance with the Superannuation Guarantee

(Administration) Act 1992.

The Superannuation Guarantee

(Administration) Act 1992 currently determines how the majority of

Australian workers have their employer contributions made to their

superannuation. Therefore, those Members or Senators who exercise the freedom of

choice the Bill provides will have their superannuation arrangements brought

into line with those applying to the wider community.

The Government

last year introduced the Superannuation Legislation Amendment (Choice of

Superannuation Funds) Bill 2002, designed to give employees greater choice

and control over their superannuation arrangements. Senators and Members are,

however, exempted from the Government’s proposed choice of fund

arrangements. By allowing Senators and Members to choose the complying fund or

RSA into which their contributions are paid, the Bill seeks to give

parliamentarians the same freedom of choice the Government has already sought to

give other workers.

The Bill will result in the funding of future superannuation accruals for

new and existing Senators and Members who elect to join another complying

superannuation fund or an RSA. It is difficult to estimate the outlays that

might be required as this will depend on how many Senators and Members choose

not to contribute to the Commonwealth under the provisions under the Act.

However, any increased cash flows do not represent additional costs to the

Commonwealth.

According to the submission of the Department of Finance

and Administration to the Senate Select Committee on Superannuation and

Financial Services’ inquiry into the Parliamentary (Choice of

Superannuation) Bill 2001 (the predecessor to the current bill), the

financial impact was described in general terms as:

• There will be

an immediate negative impact on the underlying cash budget once the first

Senator or Member exercises choice because of the payment of employer

contributions to a funded superannuation arrangement for the Senator or Member

during their parliamentary service and also, where relevant, the proposed early

roll-out of PCSS benefit will be a positive impact on the underlying cash budget

due to higher potential benefits at retirement having been

foregone;

• There will be a positive impact on the fiscal balance

from the effect of the changes on the PCSS average employer cost and the

unfunded liabilities for the PCSS. This reflects the improvement in the fiscal

balance because of reduced accruing superannuation liabilities and notional

interest expense in relation to members who opt out of the PCSS and have their

superannuation immediately funded.

There will be a long-term benefit to

consolidated revenue, and hence to the taxpayer.

Members and Senators who

opt out of the parliamentary scheme will reduce the Commonwealth’s

liability from an unfunded commitment to be paid out of consolidated revenue to

the amount required under the superannuation guarantee scheme (currently 9 per

cent of salary).

A Senate Inquiry in 1997 concluded the parliamentary scheme lacks

transparency, is out of step with superannuation practice in the wider community

and is in some cases excessively generous. In 2001, a

minor change was made, limiting new Senators and Members access to their

retirement allowances after reaching 55 years of age. No changes have been made

to address the excessive generosity of the PCSS.

The parliamentary scheme

had its origins in an era when people contemplating public office were

considered more likely to face job insecurity than the rest of the workforce.

However, in 2001 there is no such thing as ‘job security’ or a

‘job for life’ for the vast majority of the Australian workers.

The nature of modern parliamentary life means many ex-parliamentarians

are now at a competitive advantage when they re-enter the general workforce

after time in politics.

By giving Members and Senators the freedom to

opt out of the parliamentary scheme the Bill simply implements one of the key

conclusions reached by the Government members of the Senate Select Committee on

Superannuation in 1997.

On the 25th of November 1996 the Senate asked its Select Committee on

Superannuation to inquire and report on the appropriateness of the parliamentary

superannuation scheme.[2]

The

Committee received 46 submissions and held three public hearings before handing

down its report on 1 September 1997. In the report, entitled The

Parliamentary Contributory Superannuation Scheme and the Judges’ Pension

Scheme, the Committee concluded that:

• change to the

parliamentary superannuation scheme was desirable;

• the scheme was

out of step with superannuation practice in the wider

community;

• the scheme lacked transparency, and this lack of

transparency gave rise to much of the public criticism it attracted; and

• there was convincing evidence the scheme was excessively

generous to a small group of retiring

parliamentarians.[3]

According

to its report:

The Committee agreed that the scheme has many

significant shortcomings. It does not necessarily serve its members well, may

be outdated in some of its provisions and attempts to achieve too much in

relation to what a superannuation scheme can fairly be expected to

provide.

There is also a lack of transparency in parliamentary

superannuation that gives rise to much of the criticism of the PCSS. Further,

there is also clearly a negative perception in the mind of the public about the

scheme, and an uneasy relationship between the PCSS and superannuation in the

broader community. In light of these findings, the Committee considers that

reform is

desirable.[4]

Regarding

issues of flexibility, portability and choice the Committee said:

The

result of the inflexible nature of the PCSS is a lack of choice for individual

parliamentarians. In view of the increasing prospect of new members bringing to

their parliamentary life substantial superannuation as a result of other

employment, it seems inefficient as well as unnecessary to be requiring them to

contribute to a scheme which may result in them exceeding the Reasonable Benefit

Limits or exceeding their own superannuation requirements ...

The

Committee also recognises the lack of portability involved in the parliamentary

scheme. While it is possible for a member of the PCSS to purchase notional past

service that will be taken into account in determining future entitlements under

the PCSS, this option is generally not taken up. Then, on leaving parliamentary

service, there is no transferability of a PCSS pension entitlement to another

scheme.

One possible solution to these dilemmas is for membership

of the PCSS to be optional, to the extent that every parliamentarian is a member

until he or she opts out.[5]

Government members of the Committee recommended, among other

things, that upon taking office new parliamentarians should be offered the

choice of opting out of the parliamentary scheme in favour of a fully funded

accumulation scheme or retirement savings account of their

choice.[6]

The Australian Labor

Party Members of the Committee did not recommend specific changes to the scheme

but concluded the Remuneration Tribunal was the appropriate body to make

recommendations for

reform.[7]

In a dissenting

report on behalf of the Australian Democrats, Senator Lyn Allison expressed the

view that the scheme was too generous and was in urgent need of

reform.[8]

On the 1st of

December 1997 the Minister for Finance the Hon. John Fahey formally responded to

the report in a letter to the Committee’s Chair Senator John Watson. In

his response the Minister stated that:

The Government welcomes your

Committee’s report on its inquiry into the superannuation arrangements for

parliamentarians and judges. I note the committee members were all of the view

that the Remuneration Tribunal should be involved in setting parliamentary

superannuation. [9]

The

Minister went on to say that the Government would give further consideration to

the Committee’s findings in the context of changes then proposed to the

way Members of Parliament were paid. These involved setting

parliamentarians’ remuneration by reference to classifications determined

by the Remuneration Tribunal, rather than by direct linkage to public service

Senior Executive Service salaries.

Following the 3rd of October 1998

Federal election it was revealed that 33 year old Queensland Senator Bill

O’Chee, who had lost his seat after nine years service, would leave

Parliament entitled to an indexed lifetime pension of approximately $45,000 a

year. On the 7th of October 1998, in response to the public outcry over these

revelations, the Minister for Finance was reported to have pledged to review the

Parliamentary Superannuation

Scheme.[10]

On the 12th of

November 1998, the Minister for Financial Services & Regulation the Hon. Joe

Hockey introduced to Parliament the Superannuation Legislation Amendment

(Choice of Superannuation Funds) Bill 1998. That Bill proposed to amend the

Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992 to give ordinary

employees a choice as to which fund their superannuation contributions are paid.

In his Second Reading Speech to the Bill the Minister said among other

things:

The choice of fund arrangements are about giving employees

greater choice and control over their superannuation savings, which in turn will

give them greater sense of ownership of these savings. The arrangements will

increase competition and efficiency in the superannuation industry, leading to

improved returns on superannuation savings ...

The fundamentals of

this reform are that employees get a genuine choice as to which fund their

superannuation is

paid. [11]

This

legislation sought to implement a key recommendation of Stan Wallis’ 1997

report on the Australian Financial System. Recommendation 88 of that report

said in part:

Employees should be provided with choice of fund, subject to

any constraints necessary to address concerns about administrative costs and

funding

liquidity.[12]

The

Government’s choice of superannuation legislation stalled in the Senate,

since its introduction there in February 1999, and lapsed with the proroguing of

the 39th Parliament in 2001. The current version of this bill was

introduced to the House on the 27 June 2002, and the second reading debate is

due to be resumed in this spring sitting.

However, parliamentarians are

excluded from the choice arrangements proposed by the Government’s

legislation. In other words, while the Government is of the view that ordinary

workers should have a genuine choice when it comes to their superannuation

arrangements, it has not sought to extend the same freedom of choice to

parliamentarians.

When asked in Parliament on the 24th of November 1998

whether he supported a review of the parliamentary superannuation scheme the

Prime Minister replied: “I never close my mind to reviews of

superannuation, be it parliamentary or otherwise”, but went on

to conclude, “that you will never really solve the problem. I say to

those who have recently joined this place – I say this to people on both

sides – that if you imagine you will solve the anomalies of all this

within a short space of time, you will

not.”[13]

On the

8th of February 1999, in response to a Question on Notice seeking confirmation

about the review he was reported to have proposed, the then Minister for Finance

said: “the Government has not decided at this time on any review of the

Parliamentary Superannuation Scheme.”

[14]

On the 9th of March

1999 in response to another Question without Notice the Prime Minister said:

“I have never ruled, nor has the Government ever ruled out, further

examination of parliamentary superannuation arrangements.”

[15]

On the 7th of

December 1999 the Remuneration Tribunal reported to the Government on the

remuneration of Senators and Members. In its report the Tribunal recommended

that the method for setting the remuneration of Members of Parliament should no

longer be linked to the salaries of Senior Executive Service Commonwealth public

servants. Instead, the Tribunal proposed a new base payment for backbenchers

($90,000 pa) and Office Holders to be adjusted twice yearly in accordance with

increases in Average Weekly Ordinary Time Earnings index (the AWOTE). The

Tribunal concluded that with these changes it was ‘satisfied that the

remuneration package for Senators and Members (salary, superannuation, and

vehicle) is now

competitive’.[16]

However, the Tribunal gave no justification as to why

parliamentarians’ superannuation arrangements were considered

appropriate.

The predecessor to this bill, the Parliamentary (Choice

of Superannuation) Bill 2001, was introduced to the House of Representatives

on 5 March 2001. It was not given a second reading, but was referred to the

Senate Select Committee on Superannuation and Financial Services for

review.

The Committee invited public submissions through its website and

advertisements in the Australian Financial Review and the Weekend

Australian between 20-21 April 2001. The inquiry was also featured on

Channel 9’s A Current Affair on 17 May 2001.

The Committee

received 2,649 submissions and heard from 16 witnesses at a public hearing on 11

July 2001 in Sydney. Below are extracts from just two public

submissions:

No.1823: Inflation Proofing is for Politicians

Only: If my superannuation is not INFLATION PROOF why should the politicians

be so protected? If their superannuation was being eroded at the rate mine has

been they would be more responsible in their control of

inflation.[17] (B.

Hughes, Tinana, QLD).

No.1848: I am writing to lodge my objection to

the manner in which politicians receive their superannuation payouts.

Politicians are public servants and as such should be treated the same as all

Australians. The public should not subsidise their super and they should not be

able to take early payouts.[18]

(G. McLean, Kingston, QLD).

The Committee recommended “that in

order to achieve a cohesive and consistent approach, the issue of parliamentary

superannuation be considered by the remuneration tribunal as part of a

consolidated package comprising salaries, superannuation and

allowances”[19]. This

recommendation marked no departure from previously stated government and

opposition statements in this regard.

Much of this section has been extracted from the 25th Report of the

Senate Select Committee on Superannuation, The Parliamentary Contributory

Superannuation Scheme & the Judges’ Pension Scheme. For full

details of the parliamentarians’ superannuation arrangements readers are

directed to that report[20].

The parliamentary superannuation scheme provides for the superannuation

benefits of Commonwealth parliamentarians. Membership is compulsory and member

contributions are required. Benefits are paid to former Members of Parliament

or, on their death, to their surviving spouse or orphan children.

The

scheme is administered by the Department of Finance under the direction of the

Parliamentary Retiring Allowances Trust. There are five trustees – the

Minister for Finance who is the presiding trustee, plus two Senators and two

Members of the House of Representatives appointed by their respective Houses.

The parliamentary superannuation scheme was established in 1948 under the

Parliamentary Contributory Superannuation Act of that year. Reasons for

the establishment of the scheme included:

• entering Parliament

often meant foregoing potential superannuation pay-outs from previous employers

due to leaving that employer prior to retirement age;

• electoral

or parliamentary demands reduced members’ chances to re-establish careers

when their parliamentary term was over; and

• the need to entice

people to enter Parliament who would not otherwise nominate.

When then

Prime Minister and Treasurer Ben Chifley introduced the legislation in 1948 he

said:

It has frequently been said that the loss and insecurity which

attend upon service in Parliament deter men and women capable of making a

worthwhile contribution to the service of the Commonwealth from offering

themselves for election. It is hoped that this measure will help in overcoming

difficulties of this

nature.[21]

Originally

the scheme was funded to the extent of the member contributions, and was framed

along the lines of the Commonwealth Public Service Superannuation

Scheme.

Contributions were three pounds per week (about 10.4 per cent of

salary) and a fixed annuity of eight pounds per week was payable when a member

qualified for a pension, an amount which, according to Prime Minister Chifley

was in 1948: “much less than the maximum pension provided under many

private and public superannuation

schemes”.[22]

Between

1948 and 1973, the main amendments to the scheme were:

• in 1955,

the three occasions rule was introduced (see below);

• from 1959,

the age at retirement became a factor in fixing the rate of

pension;

• orphan benefits were introduced in 1959;

and

• from 1963, pensions changed from a fixed amount to being

based on salary.

In 1973 the scheme underwent major changes. The fund

was abolished and its assets transferred to the Consolidated Revenue Fund (CRF).

Contributions were then paid into the CRF, out of which benefits were also

paid.

The maximum benefit payable to a member was increased from 50 per

cent to 75 per cent of the parliamentary salary, and pensions accrued according

to the length of service rather than age at retirement. Also, the minimum age

requirement of 40 years for the pension on involuntary retirement was removed,

and the minimum age on voluntary retirement was raised from 40 to 45 years

(eventually removed in 1978). Provisions for invalidity pensions, indexation of

pensions and the recognition of State parliamentary service were also

introduced.

Since 1973, various amendments have been made including the

introduction of a 50 per cent commutation of pension option in 1978. This

option was increased to a 100 in 1979. Further changes in the same period

included:

• reducing the 100 per cent commutation option back to 50

per cent in 1983; and

• the provision for reducing a pension, on

the basis of the former parliamentarian receiving remuneration from an Office of

Profit under the Crown, was reintroduced in 1983 (it had been removed in

1973).

The level of the superannuation contributions made for parliamentarians

by the Commonwealth is set by the Parliamentary Contributory Superannuation

Act 1948. Members and Senators must contribute at the rate of 11.5 per cent

of their Parliamentary Allowances for the first 18 years in office and at 5.75

per cent for subsequent years. In addition, they must contribute the same

percentage of their Additional Office Holder Allowance if they hold a higher

office (such as ministerial).

The parliamentary scheme is also an

unfunded defined benefit scheme. ‘Unfunded’ means that the scheme

funds its benefit payments from annual Commonwealth appropriations.

‘Defined benefit’ means that members’ entitlements are, in

general, multiples of years of service and a percentage of salary. In such a

defined benefit scheme, the employer is responsible for providing the difference

between the benefit actually paid and what the member has contributed toward the

benefit.

Every three years the Australian Government Actuary provides

the Department of Finance with details of the long-term cost to the Commonwealth

of funding parliamentarians’ superannuation. At each review, the notional

employer contribution rate is reported. This rate illustrates the effective

cost of parliamentary superannuation benefits as a percentage of the total

salaries of scheme members. As at the 30th of June 1996 the rate was 69.1 per

cent.[23] The Parliamentary

Retiring Allowances Trust Annual Report for the financial year 2000-2001 puts

this figure at 69.4 per cent.[24]

This is the notional employer contribution from the Commonwealth needed

to meet the lump sums and pensions payable to retired members under the scheme.

In other words it is a three-yearly snapshot by the Government actuary of the

projected cost of scheme.

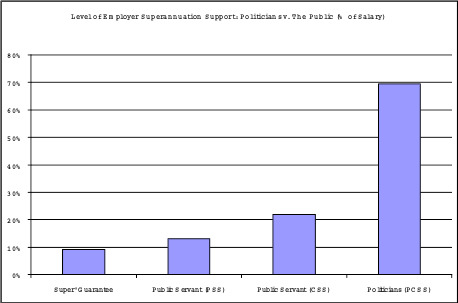

Compared to the majority of Australian workers

this level of employer contribution for superannuation is very generous. The

generosity of the scheme is demonstrated by comparing it with other

superannuation schemes operated by the Commonwealth for its public servants and

the wider public. Based on the 1996 figures, under the Commonwealth

Superannuation Scheme (CSS) the notional employer contribution was 23 per cent,

while for the Public Sector Superannuation Scheme (PSS) it was 13 per

cent.

The generosity of the parliamentary scheme is further demonstrated

when it is compared with the level of compulsory superannuation paid by most

employers under the Superannuation Guarantee (SG) scheme. The SG scheme

requires all employers to make a minimum superannuation contribution on behalf

of employees (with limited exceptions). The minimum level of employer-supported

superannuation is currently 9 per cent. When compared with the contributions

under the SG, the level of support parliamentarians receive is very generous as

the following table

illustrates.

In 1994 the parliamentary superannuation scheme was amended to make it

subject to the same preservation rules applying to other superannuation funds.

New preservation rules, administered by the Australian Prudential Regulation

Authority, took effect from 1 July 1999. From this date, all superannuation

contributions (including member contributions) and superannuation fund

investment earnings have been preserved until fund members reach their

preservation ages.[25]

In the

1997 Budget the Government announced that the preservation age would be

increased from 55 to 60 on a phased in basis. By 2025, the preservation age

will be 60 years for anyone born after June 1964, with the age 60 preservation

age being reduced by one year for each year that person’s birthday is

before 1 July 1964. This means that a person born before 1 July 1960 will

continue to have a preservation age of 55.

For the general public,

preserved superannuation benefits can usually only be accessed on limited

compassionate and severe financial hardship grounds. However, under the new

preservation rules, a person continues to be allowed to have early access to

preserved benefits where they are taken in the form of a

non-commutable[26] lifetime pension

or annuity on termination of gainful employment. It is this feature that has

allowed parliamentarians elected before 2001 to gain early access to their

superannuation entitlements. Such early access is, however, generally not an

option for most other workers until they are very close to

retirement.

This is because the generosity of the Parliamentary Scheme

(69.4 per cent of total parliamentary salaries) provides Members and Senators

with a much larger entitlement after 8 or 12 years of service compared with a

worker only receiving the SG minimum amount (currently 9 per cent of salary).

The generosity of the parliamentary scheme thus ensures that on conclusion of

his or her parliamentary service, a Senator or Member can access a much larger

non-commutable lifetime pension or annuity than other workers.

It also

means a member losing either pre-selection or an election at his or her

“third occasion” (the third election subsequent to initial election)

can access the full benefits of the scheme. In this way the scheme rewards

relatively short-term members to a far greater degree than long serving MPs.

Apart from this it encourages the “pensioning-off” of non-performing

Members or Senators.

Notes on

clauses

Clause 1 – Short title

Clause 1

provides for the short title of the Act to be Parliamentary (Choice of

Superannuation) Act 2003.

Clause 2 –

Commencement

Subclause 2(1) provides for the Act to commence

on the day that it is proclaimed.

Subclause 2(2) provides that

the proclamation cannot be made unless the Parliament has appropriated funds for

the purposes of the Act.

This measure is necessary because a private

Member may not introduce a bill requiring the appropriation of public revenue,

as an appropriation must first be recommended to the House by message of the

Governor-General. This requirement reflects the constitutional and parliamentary

principle of the financial initiative of the Crown. As Parliament considers the

Bill it may then provide for the appropriation of funds for the payments to be

made to the superannuation funds or RSAs of the Members of Parliament who choose

not to make contributions to the Parliamentary Contributory Superannuation

Scheme (PCSS). After the appropriation is made the proclamation can be

issued.

Clause 3 – Schedule

Clause 3

provides that the Acts specified in the schedule are amended or repealed as set

out in the applicable items in the Schedule.

Schedule 1 –

Amendment of the Parliamentary Contributory Superannuation Act

1948

Item 1 – Subsection 4(1) definition of

member

Item 1 repeals the existing definition of

member and replaces it with a new extended

definition.

Item 2 – Subsection 4(1) definition of non

PCSS contributor

Item 2 inserts a definition of the term

non PCSS contributor.

Item 3 – Paragraph

4(4A)(aa) deeming a Member of Parliament to be employed by the

Commonwealth

Item 3 repeals the existing deeming provision and

replaces it with a new extended provision.

Item 4 – New

sections 4G and 4H provision of choice of superannuation fund and providing for

Commonwealth contributions to the chosen fund

Item 4 inserts

new section 4G into the Act to enable a Senator or Member to choose not

to contribute to the PCSS. New subsection 4G(1) provides that a Member of

Parliament may continue to be or become a member of another complying

superannuation fund or the holder of a Retirement Savings Account (an

RSA).

New subsection 4G(2) provides that a serving Senator or

Member may cease to contribute to the PCSS on or after 1 July 2003. New

paragraph 4G(2)(a) requires a Member or Senator’s decision to be given

in writing to the Trust and stipulates that if written notice is given, the

earliest the Senator or Member could become a non PCSS contributor is the date

of that written notice.

New paragraph 4G(2)(b) applies to new

Senators and Members, and allows them to forego being a PCSS contributor upon

first entering parliament.

New subsection 4G(3) allows Senators or

Members to make their decision to opt out on first becoming entitled to a

parliamentary allowance or at any time they are a Member of Parliament. A

parliamentary allowance is any allowance as defined by section 4(1) of the Act

and is typically payable to a Member or Senator from and including the day of

his or her election to office.

New subsection 4G(4) stipulates

that once a Member or Senator has exercised their choice under the Act, they

must maintain membership of a complying superannuation fund or be the holder of

an RSA for the whole time they remain a Member of Parliament.

New

subsection 4G(5) has the effect that once a Member or Senator exercises

their choice under the Act, they will not be able to reverse their decision. The

decision to opt out of contributing to the Parliamentary Contributory

Superannuation Scheme will be permanent.

New subsection 4G(6)

provides for definitions of complying superannuation fund and RSA.

New

subsection 4G(7) provides for regulations to be made to put in place

detailed arrangements for the making of a choice under the Act and

administrative matters related to such a choice.

New section 4H

compels the Commonwealth to make contributions for the benefit of non PCSS

contributors, to the complying superannuation fund or RSA chosen by the

individual Senator or Member, in accordance with the Superannuation Guarantee

(Administration) Act 1992. This measure means that Members and Senators who

choose not to contribute to the PCSS will have superannuation contributions paid

on their behalf by the Commonwealth at the minimum rate payable, and on the

terms necessary, to avoid a superannuation guarantee shortfall under the

superannuation guarantee scheme.

Item 5 – Subsection 13(9)

definitions

Item 5 repeals the existing definition provision

for section 13 and replaces it with a new extended provision. In new

subsection 13(9) definitions of Minister of State,

office holder and person applying only in section 13

have been inserted. Each definition has a common requirement for the person to

be a PCSS contributor. The effect of the definitions is to limit the scope of

section 13 to those persons entitled to a parliamentary allowance, Ministers of

State and office holders who make PCSS contributions. Those persons who elect

not to make PCSS contributions are excluded from the requirement to make

contributions.

Item 6 – Section 18C benefits for members who

cease to make contributions to the PCSS

Item 6 inserts new

section 18C into the Act stating that the only Commonwealth benefit for

Senators and Members who choose to stop making PCSS contributions is the

superannuation guarantee safety-net amount. However, as is the case for all

other employees, this benefit must be rolled over into the complying

superannuation fund or Retirement Savings Account of the Senator or Member.

The superannuation guarantee safety-net amount has the meaning given by

section 16A of the Act.

New subsection 18C(3) puts in place

arrangements for the circumstance where a person and his or her spouse are both

members of Parliament and one of the couple opts out of the PCSS and the other

chooses to remain in the PCSS. If the partner who remains in the PCSS dies, his

or her spouse would remain eligible for payment of the spouse benefits applying

in relation to the death of the person, in spite of having opted out of the

PCSS.

[1] The Bill proposes that a Member

or Senator’s benefit on exercising their choice to opt out of the Trust

will be the ‘superannuation guarantee safety-net amount’ as defined

by section 16A of the Act.

[2] The

full Terms of Reference the Committee was asked to inquire and report on

were:

1) The appropriateness of the current unfunded defined benefit

superannuation schemes’ application to judges and parliamentarians,

including but limited to:

(a) the equity between members;

(b) the cost

to the Commonwealth and members;

(c) the impact of unfunded liabilities on

future budgets;

(d) the advantage or otherwise of member choice of fund or

investment strategy;

(e) the flexibility of existing schemes, including in

respect of portability, in the context of their working arrangements and those

applying in the general work force;

(f) the appropriateness of replacing such

schemes with a fully-funded accumulation scheme;

(g) the appropriateness of

the application of preservation rules and taxation on benefits taken prior to

age 55 to such schemes;

(h) the capacity for making superannuation

arrangements less complex than current arrangements; and

(i) the

administrative cost of such arrangements and their alternatives.

2)

That for the purpose of the inquiry the committee take evidence from the public,

Government agencies and State, Territory and Federal government departments, and

conduct public hearings as

appropriate.

[3] The

Parliamentary Contributory Superannuation Scheme & Judges Pension

Scheme, Senate Select Committee on Superannuation, 25th Report,

Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 1 September 1997, p.

41.

[4] The Parliamentary

Contributory Superannuation Scheme & Judges Pension Scheme, Senate

Select Committee on Superannuation, 25th Report, Parliament of the

Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 1st September 1997,

p.3.

[5] ibid, at

p.27.

[6] ibid, at

p.42.

[7] ibid, at

p.43.

[8] Senator Lyn Allison,

Dissenting Report, Senate Select Committee on Superannuation, 25th

Report, The Parliamentary Contributory Superannuation Scheme & Judges

Pension Scheme, Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, 1 September

1997, p.1.

[9] The Hon. John Fahey,

Minister for Finance, Government Response to Senate Select Committee on

Superannuation’s, 25th Report, The Parliamentary

Contributory Superannuation Scheme & Judges Pension Scheme, 1 December

1997.

[10] Peatling, Stefanie,

“Fahey Pledges Super Review”, Sydney Morning Herald, 7

October 1998, p.10.

[11] The Hon.

Joseph Hockey, Minister for Financial Services and Regulation, House of

Representative Hansard, 12th November 1998,

p.261.

[12] Australian

Financial System Inquiry, Final Report (Wallis Report), Canberra, Australian

Government Publishing Service, March

1997.

[13]The Hon. John Howard,

Prime Minister, House of Representatives Hansard, 24th November 1998,

p.481.

[14]The Hon. John Fahey,

Minister for Finance and Administration, House of Representatives Hansard,

8th February 1999,

p.2165.

[15]The Hon. John Howard,

Prime Minister, House of Representatives Hansard, 9th March 1999,

p.3443.

[16]Report on

Senators and Members of Parliament, Ministers and Holders of Parliamentary

Office – Salaries and Allowances For Expenses of Office, Remuneration

Tribunal, December 1999, p.10.

[17] Provisions of the

Parliamentary (Choice of Superannuation) Bill 2001 Submissions No. 1670-1897

Vol.8, Senate Select Committee on Superannuation and Financial Services,

August 2001, p.2324.

[18] ibid,

at p.2354.

[19] Report on the

provisions of the Parliamentary (Choice of Superannuation) Bill 2001, Senate

Select Committee on Superannuation and Financial Services, August 2001, p.21 at

4.16.

[20] The

Parliamentary Contributory Superannuation Scheme and Judges Pension Scheme,

Senate Select Committee on Superannuation, 25th Report, Parliament of

the Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 1 September

1997.

[21] The Hon. Ben Chifley,

Prime Minister and Treasurer, House of Representatives Hansard, 1 December 1948,

p. 3738.

[22]ibid, at p.

3739.

[23] The Parliamentary

Contributory Superannuation Scheme & Judges Pension Scheme, Parliament

of the Commonwealth of Australia, 1st September 1997, p.

15.

[24] Parliamentary

Retiring Allowances Trust Annual Report 2000/2001,

p.7.

[25] Preservation Age is the

age at which a fund member can gain access to benefits that have accumulated in

a superannuation fund or RSA, provided the member has permanently retired from

the workforce.

[26] Commutation

refers to the taking of a benefit in a lump sum.